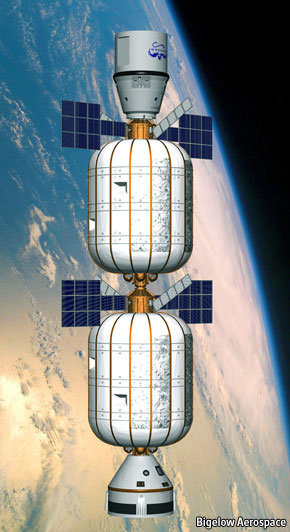

A plan to use enormous balloons to build space stations

THE International Space Station (ISS) is mankind’s holiday house in the sky. Like all such houses, it is a luxury item (costing $150 billion and rising). And like many similar projects on Earth, the owners cannot resist tinkering with it. It was in this spirit that, on January 16th, NASA announced that the ISS is to get an extension. This will not, as might have been the case on Earth, be a conservatory or loft conversion. Instead, it will be a BEAM, or Bigelow Expandable Activity Module.

Robert Bigelow, an American hotel entrepreneur and space enthusiast, has for years been pushing the idea that space stations should be made not of metal but of fabric. That would mean they could be folded up for launch and inflated in orbit.

Expandable modules may be safer, too. Ground tests by Bigelow Aerospace, Mr Bigelow’s vehicle for his orbital ambitions, suggest that the module’s walls—thick sandwiches of exotic fabrics such as Vectran (used in sailcloth and high-strength rope) and Nomex (from which fire-resistant suits are made)—offer better protection than metal ones against impacts from micrometeors and the increasing amount of artificial debris that is in orbit around Earth. They are also less likely than metals to generate dangerous secondary radiation when bombarded with things like cosmic rays. That is one reason why NASA was interested in using inflatable craft for the months-long journey to Mars.

This first station, dubbed the Alpha Station, will be equipped with laboratory equipment, workbenches and the like. Bigelow hopes to offer 60 days aboard it for around $26m, assuming that its guests make the trip into orbit on one of the cheap rockets provided by SpaceX, another private space company.

Bigelow hopes in particular to win business from governments without big space programmes of their own. To that end it has memoranda of understanding with several, including those of Britain, Japan and the Netherlands. It is also wooing the private sector, though that may prove tricky. There has long been talk of the advantages of “zero gravity” (actually, the continuous free-fall of orbit, rather than the total absence of a gravitational field) for manufacturing specialised materials whose components are of very different densities, and for growing specialised protein crystals for examination by pharmaceutical companies. This was, indeed, one of the sales pitches for the ISS. Unfortunately, the private sector stayed away in droves, and the scientific output of the ISS has been pitiful.

If renting the Alpha Station out as a laboratory does not work, there is always the option of turning it into a holiday house. Given Mr Bigelow’s background, it is often assumed that this is the plan anyway. The firm insists that it is not, at least for now. But who will really be interested in paying $26m to go into orbit remains to be seen. Inflated space stations are fine, as long as they do not lead to inflated expectations.